- Home

- Zosia Wand

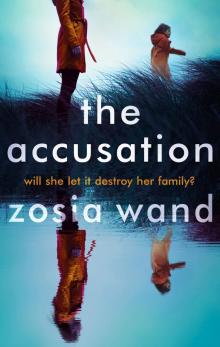

The Accusation

The Accusation Read online

THE ACCUSATION

Zosia Wand

Start Reading

About this Book

About the Author

Table of Contents

www.headofzeus.com

About The Accusation

Eve lives in the beautiful Cumbrian town of Tarnside with her husband Neil. After years of trying, and failing, to become parents, they are in the final stages of adopting four-year-old Milly. Though she already feels like their daughter, they just have to get through the ‘settling in’ period: three months of living as a family before they can make it official.

But then Eve’s mother, Joan, comes to stay.

Joan has never liked her son-in-law. He isn’t right for Eve; too controlling, too opinionated. She knows Eve has always wanted a family, but is Neil the best man to build one with?

Then Joan uncovers something that could smash Eve’s family to pieces...

Contents

Welcome Page

About The Accusation

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About Zosia Wand

Also by Zosia Wand

An Invitation from the Publisher

Copyright

For Judy Rouse, social worker, friend and Fairy Godmother, and to all those who work so hard, under pressure, to salvage families from turbulent lives. First in the firing line when things go wrong, yet seldom acknowledged for what they achieve; this book is dedicated to you. Thank you.

Prologue

I know something about fear. I know it can be red and urgent, the roar of a dragon, flames in your face. We all recognise that. You will know it as something brief and fierce, leaving smoke and ashes, sometimes scalded flesh. This fear is different. My fear is not hot and fiery, but grey and quiet, lingering in the shadows. It’s a chill breath on my neck, a whispered warning in my ear. I have no idea why it follows me. I have never experienced real danger, never suffered an act of extreme violence, but I live with a sense of something lurking. If I do the right thing, if I follow the rules and keep everyone happy, all will be well, but if I get it wrong, something terrible will pounce. I’ve learned to be one step ahead, becoming stealthy, slipping out of sight, dodging the icy drips and sidestepping the puddles. Always alert.

I sense it before the phone rings. Feel its cold grip on my hand as I try to accept the call. Neil’s name on the screen. My fingers won’t move. I have no reason to think this is anything other than the call I was expecting, to tell me that lunch is ready, that he and Milly are waiting for me. But I know before I tap the screen, before I hear the breathless panic in his voice, I know.

‘Eve?’

‘What’s wrong?’

‘It’s Milly.’

A bitter cold pressing into my back, seeping through my flesh and between the bones beneath. Please, not this.

‘She’s gone.’

1

Three Days Earlier

The ferry, from Bowness-on-Windermere to Brockhole, is crowded with families, young lovers, older couples and dogs. A large party of sleek Japanese tourists look at the world through their iPhones, framing, snapping and sharing. They followed us around the Beatrix Potter museum, exclaiming over Jemima Puddleduck and Peter Rabbit with an infectious enthusiasm that intrigued Milly more than the exhibits themselves. ‘But they’re growed up,’ she said, frowning. ‘Peter Rabbit is for children.’ We agreed it was a puzzle.

Milly is watchful, squinting in the late-August sunshine, head cocked to one side, taking it all in, her little hand in mine. The soft grip of her fingers is a new delight and I can’t help stroking my thumb up and down her plump flesh. This precious little girl. Our daughter.

‘Mummy?’ She looks at me and I wait. She smiles. That’s all she wants to say. She is trying the word out for size. Claiming it.

Mummy. Daddy. Family. Words that were never mine are suddenly resting on my tongue, sweet and round as cherries. I say them out loud, one at a time, giving them space. ‘Mummy.’ Milly nods. I turn to Neil. His rusty hair and mottled jumper are the colour of the trees that line the lake shore. He has become substantial. Over the last weeks I’ve witnessed him expanding into fatherhood. I’m reminded of the day we married, glancing at him as he walked down the aisle beside me after the ceremony, how he seemed broader, more rooted in the world. He assumes these new roles with an enthusiasm that both exhilarates and daunts me. I don’t have his confidence. I’m groping for it, hoping for it, but I haven’t found it yet.

The water glints in the sunlight. The mountains beyond are mauve and moody. ‘Daddy?’ He grins, scooping her up, and as his arms fold around her, I whisper, ‘Family,’ to myself. Those arms that have held me while I wept. That solid chest I have leaned against, listening to the steady beat of his heart. That love we shared has grown to envelop this girl. Our daughter.

Milly has been with us since the beginning of June. Almost three months. I still can’t quite believe they’re letting us have this beautiful child. They trust us. We’ve been approved. In just over a month we’ll be able to apply to the magistrates’ court for an adoption hearing where it will all be ratified. After years of not being the lucky, the chosen, the blessed, after disappointment and bewilderment and the not knowing why, the brutal, not this time, not you, we’re finally going to be given this opportunity. We’re so close.

Will that be the moment when I believe?

Neil rests Milly on his hip, pointing out the boathouses that decorate the shoreline. The chair of my board lives in one of these grand old houses, but I have only approached the property from the road side and cannot get a sense of perspective from the lake. We have been invited for tea, once Milly’s settled in, but for the time being it’s just the three of us, getting to know one another, forming a world Milly can claim for herself. A safe place, as Shona explained, at the last review meeting. Milly needs time to establish her relationship with us before we can introduce anyone else.

Shona is more than a social worker. Hers is not the kind of job where you can tick the box and switch off the light at the end of the day. Her heart is invested in the families she creates. She is Milly’s Fairy Godmother. Our Fairy Godmother, and I hope she’ll remain part of our lives.

Adoption was always on the agenda, for us, whether we had our own children or not. Neil is adopted, his sisters aren’t. We’ve seen a mixed family can work. While other couples might have kept hoping, investigated, turned to IVF, we simply sketched our dreams elsewhere and they exerted their own romantic pull. I’ve accepted that we may never have a child with Neil’s eyes, or my smile, but with Milly we have something unique and equally precious in its own way; a little girl full of love and hope and her own personality waiting to be discovered. We have an adventure. I believe she was al

ways waiting for us to find her, that some greater force out there was pulling us together. Romantic nonsense to some, but my story. My comfort.

Adopting Milly wasn’t difficult or torturous. We looked forward to Shona’s visits, the discussions that ensued. Our confidence grew. They wanted us as much as we wanted to be accepted by them. And there was Milly ready and waiting. Four years old with gold freckles and a neat fringe, frowning at the camera as if trying to work out a puzzle. A little girl brought up, for the most part, by her maternal grandparents, until Nana had a stroke and could no longer manage. Milly’s mother has a heroin addiction and no one knows anything about her father. Shona phoned from the council offices in Kendal to deliver the news that we’d been approved, and followed her congratulations with, ‘There’s a little girl we think might be just right for you.’ She came straight over with the photograph. It was that quick. It isn’t always this way; sometimes it can take months before a match is made, but we were lucky. This was clearly meant to be.

‘You OK?’ Neil is watching me, searching my face.

I nod to reassure him. Milly points to a line of ducks making their steady way up the lake. I run my hand along her hair. I’m allowed to do this. Around me people will assume I’ve been doing it all her life. When we met Milly she was a stranger. I’d prepared myself to feel compassion, concern, possibly affection, but not love, not straight away. I expected that to be something that would grow, quietly, over time, for us and for her. But it’s not like that for Milly. Her love is uninhibited, wild, provoking an instinctive affection that spills out of me. I find this a little overwhelming, almost frightening, because I haven’t earned this love. It may not be real. It may simply be her enthusiastic response to this new world, a fantasy she’s created, and our reality may yet disappoint. My fear fidgets in shadows. I feel it in the unexpected chill beneath the trees, a sharp reminder that this joy I’m feeling may yet be snatched away.

We’re approaching the jetty. People are getting up, collecting their things. Neil lowers Milly to the deck and takes her hand, telling her how we came here at Easter, before she was part of our lives. That was less than five months ago, before we knew we’d be approved, before we knew anything about Milly. We’d brought a picnic, having no family obligations and no children to entertain. We’d sat in our matching camping chairs wrapped in hats and scarves and watched a vast family of three generations with a dozen grandchildren hunt for chocolate eggs. The kind of family I read about as a child, and longed for.

We alight at Brockhole, Milly swinging between us. As we clear the trees, she catches sight of the adventure playground and drops our hands with a shriek of excitement, charging forward, but after a few paces she hesitates, turning to look back, her face etched with that frown of uncertainty we’ve come to recognise.

‘It’s OK,’ Neil calls after her. ‘We’re right behind you.’

She skips off with a grin, delight bursting out of her in little leaps and twitches. Neil raises the camera that’s slung around his neck. We’ve taken so many photographs. If Milly had been born to us, would I be so aware of this joy? It’s different with a baby, of course, but would I have been able to take it for granted? This chapter of our lives is unique and I’m so grateful for this gift. As Milly runs towards the wooden towers, tunnels and frames nestled beneath the green-gold trees, I’m silently filming that moment in my mind, to return to, years from now. Raising the camera to his eye, Neil captures it.

Milly is perfect. It’s as if we’d conjured her. A little girl with chestnut hair and intelligent, curious eyes, looking for her Forever Family and seeing that possibility in us. And maybe sometimes it is like that. Maybe Neil’s right, and after a lifetime of having to be patient, of swallowing my disappointment, dusting myself off and starting again, maybe this really is my time. But part of me is still afraid that it’s all been a little too easy. Luck is something that happens to other people. I’ve always had to earn my joy and I’ve not yet earned this.

Neil slides his arm around me and I rest my head into the cradle of his shoulder as we walk along. ‘Happy?’

I snuggle in closer by way of reply. ‘It’s all happened so quickly. I’m still trying to catch up.’

‘The six months of assessment wasn’t enough for you?’

I shrug. He wrinkles his nose in sympathy. He knows me. I’m a cautious person. Throwing myself at life is not my style. The adoption process began in a leisurely way and whilst I was impatient and wanted a family, I had adjusted to that rhythm. The weekly meetings, then waiting for Shona to complete our application, for it to go to the panel, another month for the panel to meet and approve us, but as soon as we got the approval, the snowball took off at breath-snatching speed. We were presented with Milly’s paperwork that same day and within the month the match had been agreed and introductions begun. I’ve gone from being a potential adopter to being the mother of a four-year-old in a matter of weeks.

The sun is out. The lake is a glass pool reflecting smudged mountains. This is where we live, this place the tourists come to snatch in moments and photographs. This is our home and I’m here, with the man I love and our daughter, surrounded by families making the most of the last days of summer. I drink it up greedily, grateful for every precious moment. I’m enjoying Milly, this instant family we’ve created, this thoughtful girl with the serious gaze that’s suddenly interrupted by the splash of a smile. I will not let the lurking fear in.

And then I see her. A grey-haired woman, sitting at a picnic bench, unwrapping a round of sandwiches. She’s not my mother, but she could be. It’s the sandwiches, the greaseproof paper and her grey hair, coarse waves brushed back from her face. It could be her, but it isn’t.

She’s with two children: a boy, younger than Milly, maybe two or only just three, and an older girl of about five with a thick ponytail. Two children, out with their grandmother. Milly talks about her Nana and Gramps constantly. They had a special bond, and, as far as possible, we hope to maintain this through supervised visits, but it will never be the same and we have been warned that Nana’s health is deteriorating. We are a distraction for the time being, but the loss for Milly will be immense and we will never be an adequate replacement. Grandparents are important. As a child I remember longing for my own silver-haired supporters proudly attending school events, or waiting patiently for me in the playground with sweet treats and delighted smiles. My maternal grandparents died before I was born and I have no memory of my father or his family. The boy is kicking his legs backwards and forwards under the bench. His dark hair hangs low over his eyes in thick waves. His sister is slipping away, back to the climbing frames and slides. Her grandmother calls to her, but she is shaking her head, the ponytail bouncing. She doesn’t want the sandwiches, she wants to play.

This is what happens. I’m happy for a moment and then suddenly something snatches it away. This is not my mother. My mother is not here.

Neil squeezes my hand. I glance up. He’s seen what I’m looking at. He pulls me closer and I allow myself to be comforted. This is about us, I tell myself. We’re here, Neil, Milly and I, and that’s enough.

Milly has shoved open the gate and is barrelling across the playground to the tyre swings. There’s one swing hanging empty and she’s heading straight for it, but the little girl who has run away from the sandwiches sees Milly’s target and she’s closer. She decides to intercept and grabs the chain, pulling the tyre towards her as Milly approaches. I freeze. Milly jerks back and stops. There’s a standoff. I want to run over and wrestle the swing from the older girl. She didn’t want to swing until she saw that Milly did. This child is spiteful, she’s cruel. I want to shove her aside and let Milly climb on, and as if he’s read my mind, Neil pulls me back. I try to shake him off, but he’s stronger than me. ‘Don’t,’ he warns.

I wouldn’t. This is a child. I’m not a monster. I’m surprised by the vehemence of my response. This isn’t like me. ‘It’s not fair.’

‘Why don’t we see wh

at Milly does?’

What Milly does is admirable. She asks the girl politely if she can have the swing. The girl shakes her head, but she doesn’t get on the swing herself. She stands, holding it away from Milly.

I wait for Milly to turn to us for help, already rehearsing the scenario in my head. I will walk over, smiling. I will introduce myself and Milly to the girl and ask her name. I’ll suggest they sit on the swing together.

But Milly doesn’t turn around. What Milly does is to drop her head down and charge at the girl, knocking her backwards onto the loose wood chippings that form a protective layer over the tree roots and hard ground. Neil is the one to run forward, leaving me standing, gaping and useless. It’s Neil who dusts the girl down and leads her, sobbing, back to her grandmother, with Milly dragging along beside him protesting. ‘She maked me do it! She’s nasty!’ It’s Neil who insists Milly apologise.

‘Say sorry, Milly, or we will get straight back on the ferry and go home.’ His voice is firm and carries on the breeze. And he insists she repeat her apology, sincerely, before it is accepted.

I watch all this in horror. I do not know how to do this.

What would my mother have done? I try to imagine her here. She would be confident. She wouldn’t hesitate. She wouldn’t stand here like a lemon unable to move.

I watch the grandmother reassure Neil that it isn’t a problem. I watch her question her granddaughter. She’s quite stern. Is she asking her why she stopped Milly having the swing? Is she suggesting Milly isn’t the only one who needs to apologise? I can see she’s addressing both girls and they seem to be listening. As I watch, the older girl holds out her hand and Milly takes it. They turn and skip back towards the playground together. For them it’s all over. Neil says something to the grandmother and she laughs.

I stand in the playground, watching Milly on the swing with her new friend, and I feel utterly alone. The ache is sudden and fierce. A need to see my mother. To be with her. I need to talk to her about Milly, to tell her everything that’s been going on, to share these feelings, these waves of emotion I hadn’t anticipated: love, joy, gratitude, delight, but also my fear.

The Accusation

The Accusation