- Home

- Zosia Wand

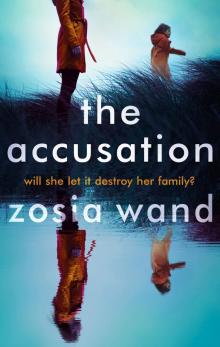

The Accusation Page 13

The Accusation Read online

Page 13

‘We were not cool!’

She looks offended. ‘I was cool. You were cool by proxy.’

I have to concede. Naz always had style. A flair with vintage clothing. ‘Fancy dresses from the time your nana and grandma were girls,’ I explain to Milly. ‘And hats.’ I grin at Naz, remembering the trilby and the little flowerpot hat that sat close to her skull, accentuating her cheekbones, and the great floppy seventies number with the silk scarf trailing behind it. ‘You wore great hats.’

Naz nods, pleased, then looks down at herself and pulls a face. A faded pair of jeans and a white collarless shirt, but even this has been lifted by a silk scarf loosely draped around her neck, a flash of electric blue. She’s filled out and toned things down a little, but she’s still got style and when I tell her, she lights up, delighted.

Milly interrupts us. ‘Tell me the story!’

I’m suddenly shy. I’ve never told this story before. When people ask how Neil and I met, I simply tell them he was a lifeguard at the pool. It’s a fact, not a story. Milly is watching me, waiting.

Naz says, ‘Your daddy was sitting up on that giant chair.’ She points to the lifeguard looking down at us and gives him a wave. He doesn’t wave back, probably still a little grumpy about our earlier misdemeanour. Milly is impressed. The lifeguard is clearly an important person. Naz looks at me, weighing things up. She’s waiting for permission. I’m interested to hear how she’s going to present this story. I give a nod. She grins. ‘Your mummy was sunbathing by the side of the pool, looking beautiful and glamorous.’ I snort with laughter, but Milly is drinking it up. Was I beautiful? I didn’t feel it. I remember, too clearly, being horribly conscious of my wobbly white thighs, holding in my belly, envying Naz’s taut dark flesh, the way she delighted in her environment with no thought for how she looked. Diving into the water, slicing her way up and down the pool, hoisting herself out, shaking her hair over my goosepimpled, dimpled flesh, honking with laughter, drawing the attention of everyone around us, while I squealed and hid myself beneath a towel. Naz was lean and solid; I was curved and soft. Naz was confident and challenging; I was achingly shy and prone to extreme blushing.

‘What happened?’ Milly prods.

Naz hesitates. I wait. ‘Your mummy didn’t want to go in the water.’ It was cold. I remember I’d recently permed my hair, at home, very badly. I struggled with my hair as a teenager. Neither curly nor straight, I’ve learned, over the years, that I can pretty much leave it to its own devices, but I didn’t have the experience or the confidence back then to allow it to do that. My hair was caked in gel and I was terrified the pool water would either turn it into rock-hard ringlets or an unmanageable frizz. ‘I dragged her in. She was kicking and screaming and clinging to her towel, making a terrible fuss.’

I took the towel in with me. I remember falling sideways, my leg hitting the pool edge, an almighty splash as my ungainly lump broke the surface, water shooting up my nose, struggling to right myself, the sodden towel wrapped around my arm. Flailing, furious. A hand reaching down into the water. Long, lean fingers wrapped around my wrist. The force of that grip. Kicking, shaking the towel loose, feeling his strength pulling me up, my face breaking the surface, gasping for air. Blinking, clearing my eyes to see him staring down at me, the wrinkled concern opening out into a smile. Rusty hair and freckles. He stopped pulling, but didn’t let go of my wrist, just stayed absolutely still, waiting for me to catch my breath, smiling patiently.

‘Your daddy,’ Naz continues, ‘jumped down from his throne and rushed to rescue the drowning girl.’

‘Did he dive in?’

Naz snorts. ‘Oh no. He didn’t have to dive in. She wasn’t really drowning, just making a lot of fuss to get his attention.’

‘That’s not true!’

Naz ignores me. ‘He reached down and pulled her out.’

He tried, but I was too heavy for him. I had to swim to the steps and climb out, once I’d retrieved my towel from the bottom of the pool, but I don’t want to spoil the story.

Milly beams at me, delighted. Naz watches the two of us. I can see she’s itching to carry on and tell Milly how Neil turned on her. How he reprimanded her like a schoolteacher, humiliating her in front of everyone at the poolside, threatening to have her banned if she ever did anything as stupid and reckless as that again. But she stops, generous enough to give Milly the edited story, knowing that she doesn’t need to tell me how embarrassed and furious she felt in that moment and how it’s coloured her opinion of Neil ever since.

She watches me, waiting for the memory to pass between us. I give her a sympathetic smile, let her know I’m grateful for the editing and change the subject. ‘Do you remember Tina Lord?’

Naz shakes her head. ‘Why?’

I glance at Milly. Naz gets the message. ‘Max, take Milly down to the shallow end and show her your handstand.’ Milly runs straight off, but I call her back to put on her armbands. She pouts and points to Max.

‘He isn’t wearing armbands.’

‘Max can swim. We’ll organise lessons as soon as we get home, I promise.’

‘So,’ Naz leans forward as soon as Milly’s gone, eyebrows raised, ‘who is Tina Lord?’

I tell her about Mum’s set-up with Ann Lord in the café. Naz frowns. ‘Neil’s never mentioned her?’ I shake my head. She shrugs. ‘Ask him.’ I chew my lip. She watches me. ‘Why can’t you ask him?’ Too sharp. She knows it’s not as simple as that, but she gets impatient when I talk about Neil. To be fair, I did, pretty much, abandon her when he came on the scene. Before Neil, Naz and I were a team, and suddenly I had someone else. She didn’t have a boyfriend, said she preferred it that way, though I think some of that was bravado. Naz is full-on and she was a bit much for a lot of boys our age. She raises a fuzzy eyebrow sceptically and says, in an Inspector Poirot voice, ‘You think he’s hiding something?’

‘Stop it!’

She leans back, as if I’ve pushed her away, resting on her hands, reading me.

I’ve overreacted. She isn’t suggesting anything sinister. There’s always been friction between her and Neil. He follows the rules she flouts. He’s a suit and tie man; she’s a dance naked down the street woman. But there’s more to it than that. Neil thinks Naz is a bully. Not intentionally, but she’s a strong personality and used to getting her own way. I was shy and pliable. She was the one in control until Neil stepped in.

Things eased up once she got together with Stu. He’s nearly ten years older than us, calm, easy in his own skin. He sees through all the colour and noise that Naz hides behind, to the loving, loyal woman inside. To do that requires a degree of tolerance that Neil just doesn’t have. He couldn’t see that Naz’s attitude to him was defensive, a need to show she didn’t care, when really, at heart, she was hurt. I let her down. I still feel guilty about that, but I fell in love with Neil, and he was good for me. I felt safe with him in a way I’d never really felt safe before. I know Naz loves me, but she could be impatient and, albeit unintentionally, cruel at times. Neil was always kind. And he offered me an escape from Mum. The travelling, the freedom, the possibility of living a different life. I know Naz understands all this, but she will never forgive Neil for taking me away. She was the one who was meant to escape this small town and claim the world, not me.

‘You should come to Tarnside,’ I say, meaning it, though I can’t picture how it could happen. ‘Bring Stu and the kids. We can make it work.’

‘Maybe.’ But she won’t.

‘Come on your own. Let Stu have the kids for a couple of days.’

‘So we can paint your little market town red?’ Tarnside? Where would we start? Tequila slammers at the Crown’s quiz night? A burlesque number during the interval at the Roxy? She tilts her head to one side. ‘Why have you come down without Neil?’

‘Mum had a fall. Couldn’t walk apparently.’

Naz snorts and I feel a little guilty. Mum was clearly in a lot of pain when I left today, sitting with her foot up, having overd

one it yesterday. It’s all right when I’m critical of her, but when Naz or Neil start, I always feel the need to defend her.

She’s thoughtful for a moment. ‘Are you worried about Tina Lord?’

I shake my head. She frowns, watching me, as if she’s waiting for something, but I’m not sure what she’s driving at. ‘Be careful, Eve.’ She hesitates. That cold drip-drip-drip. Goosebumps on my flesh. Her dark eyes are intense. ‘You have a family now. You need to protect that.’ I’m not sure what she means, but I’m too frightened to ask.

16

Naz is distracted by Cam who’s manoeuvred his way towards the pool edge some distance from us to watch the other children playing. She grabs his buoyancy aid and follows him. Milly leaps, bringing her knees up to her chest, and bombs into the water with an almighty splash. Her skinny arms slice the air as she comes back up, her face stretched to the sky, gasping. With a bit of help she’ll be swimming like a fish.

Naz throws herself back down onto her towel. ‘Look out. Lesley Butler has spotted you. I give it three minutes and she’ll be over here, getting the gossip. If it was just me and the boys she’d pretend she didn’t recognise me, but you, my darling, are too much to resist.’

Lesley was a classically cool girl at school. The right hair, the right clothes. The girl my mother would have preferred me to choose for a best friend. She was frighteningly sorted in a way that Naz and I never were, always one step ahead, been there, done that, prepared. Not adventures, but calculated steps. Everything was always controlled with Lesley; she passed her driving test, got a job, bought a car, bagged an attractive, if boring, boyfriend with career prospects, got engaged and invited us all to the party. A proper party that was almost a wedding itself, in a hotel with waiters and canapés. She got a mortgage for a pretty little terraced house, had the wedding. Naz and I weren’t invited to that (I think we failed to be sufficiently appreciative of the engagement party). She’s clearly had the babies too. Girls. One in her early teens looking a little sullen and aloof, the other two or three years younger, licking an ice cream and pulling faces at her sister. Lesley looks much the same. Her hair is shorter, straighter, blonder, but she’s still slim and elegant and a little snooty. She’s getting to her feet.

‘Told you,’ says Naz, as Lesley picks her way between the towels and camping chairs.

‘Hello? Is it Eve? Eve Leonard? Oh my God! Eve Leonard!’ She claps her hands together and does a little jump like a grown-up Shirley Temple. ‘I don’t believe it!’

‘You’d better believe it,’ says Naz, tartly.

Lesley ignores her. Milly is climbing out of the pool, heading towards us, dripping. ‘Is this your daughter?’ I feel stupidly delighted to be able to say yes to this question. Yes, Lesley Butler, I am a mother; I’ve joined the golden club at last. ‘Oh, my God!’ She claps again and bends down, from the waist, not crouching the way Dawn from next door did, but bending at the middle, with her legs straight, looking down. ‘What’s your name, darling?’

‘Milly.’

Lesley beams at me. ‘She’s adorable!’

I think Milly is adorable. But would she be to anyone else? All she did was say her name and yet I’m delighted by this praise. I’m inexplicably proud that Milly has impressed Lesley Butler.

‘I didn’t know you had a daughter?’

So this is it. Lesley will have heard on the Hitchin grapevine, she saw me in Hitchin, while I was still living here, without any children. Lesley wants the story and though it’s a story I should be happy to tell, a story I’m usually eager to tell, I don’t want to tell it to Lesley. I don’t want to see her clap her hands and say how perfectly lovely all this is. It’s Milly who says, ‘I’m adopted.’

Lesley’s face creases with concern. ‘Oh, darling. You poor little mite!’ and before I can react to this, looking at me, ‘Couldn’t you have your own children then?’

‘Milly is my child.’

‘Of course. Of course, she is.’ She smiles a plastic smile.

I want to carry on. I want to say that she is not a ‘poor little mite’, but I don’t want to draw any more attention to this crass statement in front of Milly. ‘How old are your two?’ I ask as I imagine yanking her head back with a handful of that glossy hair. The violence of this image startles me. I’m not that person, I’ve never been violent, yet something deep inside me has begun to stir; a low growl rumbles through my veins.

Lesley glances back, as if to check they’re still the perfect-looking specimens she left behind. ‘Iris is thirteen and Violet is almost eight.’ Iris chooses that moment to reach across and casually yank the beach towel from under her sister, sending her toppling onto the concrete with a yelp of indignation. Lesley laughs a little stiffly. ‘Sisters! Mine was the same. Always teasing. She loves Violet really.’

Naz yawns and says sleepily, ‘I was going to call Max Nasturtium if he was a girl. Wild. Bold. Into everything.’ Lesley frowns, unsure if Naz is serious or not. I keep my eyes fixed on Iris and Violet. Naz, always one to take it that step further, continues, ‘And Cam over there, he’d have been a dandelion. Pain in the arse weeds. Can never get rid of them.’

Lesley draws back. She just about manages to hang onto her smile. ‘I’m sure you don’t mean that.’

‘I do,’ says Naz, that blade in her voice right at the surface now. ‘You try changing a nappy a ten-year-old’s shat in and you might feel the same.’ Lesley’s smile crashes to the ground. And though Naz has scored, it’s an own goal and she knows it. I watch her glance over to Cam, her face a silent apology.

Lesley swallows and turns to me. ‘Well, it’s been nice seeing you, Eve.’ She resurrects the smile for Milly. ‘And you, Milly. You are a lucky little girl.’

I hug Milly to me and say, ‘We’re the lucky ones,’ but what I want to say is that it has nothing to do with luck. That Milly deserves to be loved and nurtured just like any other child. Why should she consider herself lucky?

Lesley nods, ‘I do admire you,’ and the growl rolls out inside me and I want to roar into her smug little face, but I don’t. I turn on my professional voice and wrestle control. ‘There’s nothing to admire. We wanted a family. Adopting Milly has given us a family. It was entirely selfish.’

Naz says, ‘Do you admire me?’

Lesley hesitates. She glances at Cam and quickly away again. ‘Of course.’ But she doesn’t. Here is Naz, playing the brutal card that life’s dealt her. Brave. Patient. Self-sacrificing. But Lesley doesn’t see that as admirable. It’s as if Naz is somehow to blame for the situation she’s in. Unlucky. Tarnished. Whereas I’m to be admired. Where’s the justice in that? I feel I should say something in Naz’s defence. Something sharp and witty that drives the point home, as Naz would do for me, but I lack her skill.

Lesley says, ‘Well, it was lovely seeing you. Have you moved back from wherever it was you went, or are you just visiting?’

I run my hand down Milly’s warm back. ‘Visiting.’

She nods. ‘Well, see you next time.’ With a little wave, she swings back to her girls.

Naz says, ‘She always was a bitch.’ She looks at Milly. ‘Sorry. You didn’t hear that.’

‘I did,’ says Milly, matter-of-factly, adding, ‘I’ve heard worse.’

We laugh. I assume this is her nana’s phrase. I don’t like to think what Milly’s heard in her life that she should not have heard, or seen. No doubt we’ll discover it over time. Her grandparents were pretty good at protecting her. She’s a well-balanced, confident little girl. It could have been so much more difficult. Apart from the odd showdown over clothes and chicken that isn’t coated in orange breadcrumbs, Milly has been happy with us. I grab hold of her and squeeze her to me, losing my balance, so the two of us roll onto our backs, laughing up to the sky. She is so delicious. So bright and funny and spilling over with love. Why can’t my mother appreciate that? Why can’t she share in my joy over this child?

Tears prick my eyes and I sit up, blinking them back f

uriously, but Milly’s seen. Her forehead puckers. ‘You’re crying again!’

Naz’s head snaps round. I turn away. ‘No, I’m not. I just laughed a bit too much.’

Max is at the far end of the pool, preparing to dive. Three little girls with bouncy ponytails wait, their skinny legs dangling over the side, toes skimming the water. I sniff, shake myself and try to laugh it off. Naz digs around in the enormous bag she’s brought and pulls out her purse. ‘Milly, go and prise Max away from his fan club and tell him to get us all an ice cream.’

Eyes huge, Milly snatches the note from Naz’s hand and dashes off before she can change her mind.

Naz doesn’t ask me what’s wrong, she doesn’t have to. We’ve been friends for thirty years. Not all language is spoken. ‘I don’t know what’s the matter with me,’ I say, swallowing more tears, struggling to contain this sudden typhoon of emotion. ‘Why can’t I just be happy? I’m so quick to judge Mum, but she was struggling to manage alone, working full time. She did her best.’ Naz waits. I’m not making sense. ‘She’s so… indifferent. I thought she’d love Milly. How can she not love Milly?’

‘Because she’s jealous.’

‘Jealous?’ Of me? It’s possible. Mum was a single parent. I have Neil to support me, to talk to, to lean on, and on a practical level, to bring in some of the money and to do stuff that I don’t understand or want to understand, like fiddling with the boiler to make it work or changing the wheel on the car if we get a puncture. Typical boy stuff, of course, which makes me wince. I’m such a cliché! I remember Mum having to go out, in her dressing gown, in the middle of the night, to knock on our neighbour’s door because she’d discovered a leak in the hot water tank and was worried it might flood the house before she could get a plumber out in the morning. The humiliation of having to ask for help from a man she detested, who made a ritual of griping about the birds she fed because they made a mess on his patio. I can remember the pinched fury of her body as she mopped up after he’d left.

The Accusation

The Accusation